Tribal History

Hundreds of years ago, long before white men came to this land, these mountains, plains and deserts belonged to the Mescalero Apaches. No other Native Americans in the Southwest caused the terror and constant fear in the settlers as the Apaches did throughout their existence. They raided Spanish, Mexican and American settlers, and were known to be expert guerrilla fighters who defended their homelands.[no_toc]

The Mescalero were essentially nomadic hunters and warriors, dwelling at one place for a temporary time in brush shelter known as a “Wicki up”; short rounded dwellings made of twigs or teepees made of elk hides and buffalo hides. The Mescalero roamed freely throughout the Southwest including Texas, Arizona, Chihuahua, México and Sonora, México.

The Mescalero were essentially nomadic hunters and warriors, dwelling at one place for a temporary time in brush shelter known as a “Wicki up”; short rounded dwellings made of twigs or teepees made of elk hides and buffalo hides. The Mescalero roamed freely throughout the Southwest including Texas, Arizona, Chihuahua, México and Sonora, México.

Today, three sub-tribes, Mescalero, Lipan and Chiricahua, make up the Mescalero Apache Tribe. We live on this reservation of 463,000 acres of what once was the heartland of our people’s aboriginal homelands.

Reservation History

The Mescalero Apache Reservation – long recognized by Spanish, Mexican, and American Treaties – was formally established by Executive Order of President Ulysses S. Grant on May 29, 1873. Mescaleros on the reservation numbered about 400 when the reservation was established more than 100 years ago.

Survivors of the Lipan Apaches, a tribe which suffered heavily in the Texas wars, were brought from northern Chihuahua, Mexico about 1903. In 1913, approximately 200 members of the Chiricahua band of Apaches came to the reservation. They had been held prisoner at Fort Sill, Oklahoma since the capture of the famed Apache Geronimo in 1886. All became members of the Mescalero Apache Tribe when it was reorganized under the provisions of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act.

Today’s Mescalero Apache Tribe is governed by a Tribal Council of eight members with an elected President and Vice-President. Each official is chosen for a two-year term by secret ballot. Authority and responsibilities of the Tribal Government are defined in the Constitution of the Mescalero Apache Tribe, as revised January 12, 1965.

Early Apache Warriors and Chiefs

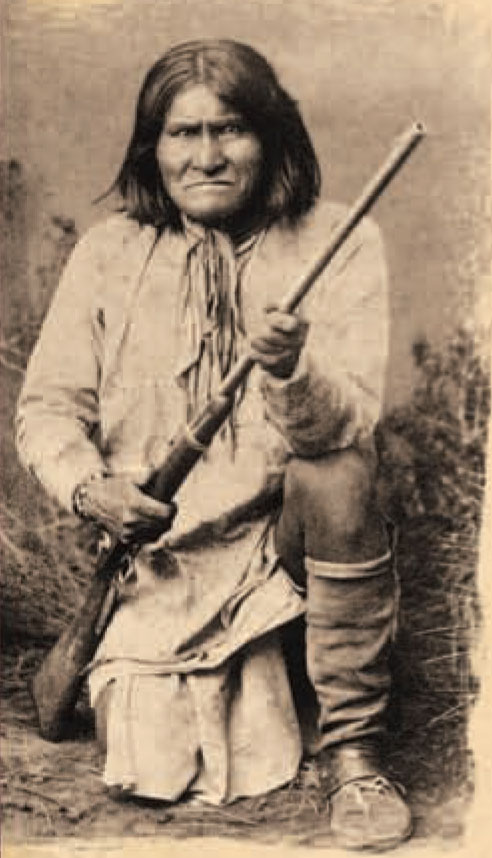

Geronimo (1829-1909) was born in present-day New Mexico at the head waters of the Gila River. Geronimo was the last warrior fighting for the Chiricahua Apache. He became famous for standing against the U.S. Government and for holding out the longest. He was a great spiritual leader and medicine man. Geronimo was highly sought by Apache chiefs for his wisdom. He is said to have had supernatural powers. Geronimo could see the future and walk without creating footprints. He could keep the dawn from rising to protect his people.

Geronimo (1829-1909) was born in present-day New Mexico at the head waters of the Gila River. Geronimo was the last warrior fighting for the Chiricahua Apache. He became famous for standing against the U.S. Government and for holding out the longest. He was a great spiritual leader and medicine man. Geronimo was highly sought by Apache chiefs for his wisdom. He is said to have had supernatural powers. Geronimo could see the future and walk without creating footprints. He could keep the dawn from rising to protect his people.

Geronimo’s final surrender in 1886 was the last significant Apache guerrilla action in the United States. At surrender, his group consisted of only 16 warriors, 12 women, and six children. Following his surrender, Geronimo and 300 of his fellow Chiricahua were shipped to Fort Marion, Florida, and became prisoners of war for 27 years. On February 17, 1909, Geronimo died – unable to return to his homeland. He is buried in the Apache Cemetery in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. His descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation today.

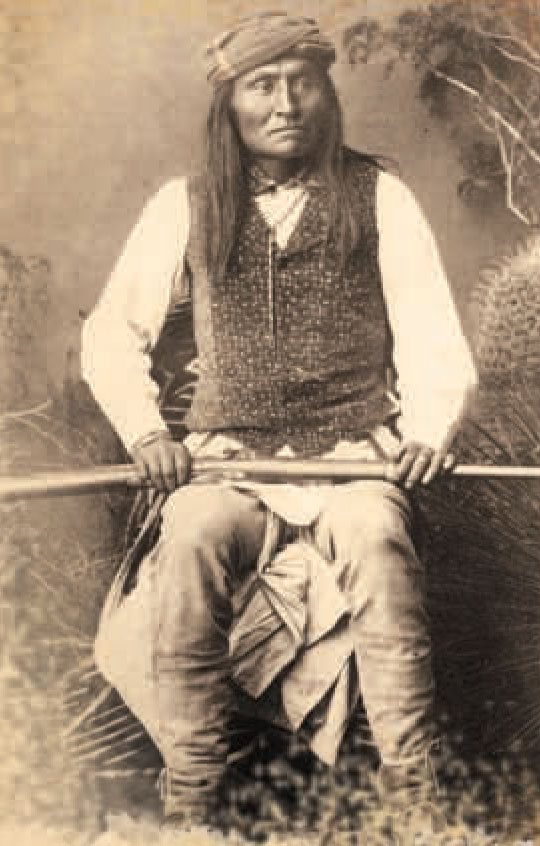

Mangas Coloradas (1797-1862) was a Chiricahua Chief and natural leader because of his intelligence and size. Unusually tall, he was over six feet in height. Mangas united the Apache tribes and led them in a successful war of revenge and cleared the New Mexico area of white settlers. When the Americans took possession of New Mexico in 1846, he defended Apache Pass against General James H. Carleton’s California Column. Leading his warriors in continuous warfare until 1862, he was killed by Union soldiers at Fort McLane. Today his descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Mangas Coloradas (1797-1862) was a Chiricahua Chief and natural leader because of his intelligence and size. Unusually tall, he was over six feet in height. Mangas united the Apache tribes and led them in a successful war of revenge and cleared the New Mexico area of white settlers. When the Americans took possession of New Mexico in 1846, he defended Apache Pass against General James H. Carleton’s California Column. Leading his warriors in continuous warfare until 1862, he was killed by Union soldiers at Fort McLane. Today his descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

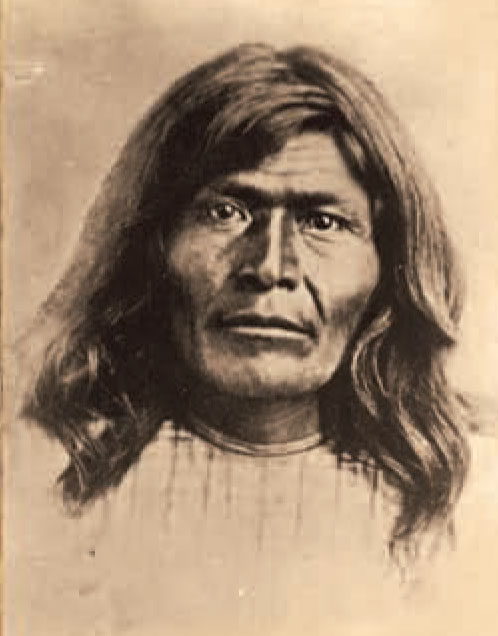

Victorio (around 1825-1880) was a Chiricahua Chief of the Warm Springs Apaches. When his people were removed from their ancestral home to the desolate reservation at San Carlos, Arizona, Victorio bolted for México with a group of followers. He and his people terrorized the border country with continual raids. Victorio always managed to elude his pursuers. In October 1880, Victorio died at a place called Tres Castillos while waiting for a small raiding party to acquire ammunition they needed. Victorio was taken by surprise when General Joaquin Terrazas and his army attacked Victorio and his band of 78 Apaches. His descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Victorio (around 1825-1880) was a Chiricahua Chief of the Warm Springs Apaches. When his people were removed from their ancestral home to the desolate reservation at San Carlos, Arizona, Victorio bolted for México with a group of followers. He and his people terrorized the border country with continual raids. Victorio always managed to elude his pursuers. In October 1880, Victorio died at a place called Tres Castillos while waiting for a small raiding party to acquire ammunition they needed. Victorio was taken by surprise when General Joaquin Terrazas and his army attacked Victorio and his band of 78 Apaches. His descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Lozen (late1840s-1886) was a Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache and a skillful warrior; a prophet and an outstanding medicine woman. She was the sister to Chief Victorio. She was also known as a “shield to her people.” History has it that Lozen was able to use her powers in battle to learn the movements of the enemy and that she helped each band of Apaches to successfully avoid capture. After Victorio’s death, Lozen continued to ride with Chief Nana and eventually joined forces with Geronimo’s band until she finally surrendered with the last band of Apaches in 1886. She died of an illness in Mount Vernon Barracks in Mobile, Alabama. Today, Lozen’s descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Lozen (late1840s-1886) was a Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache and a skillful warrior; a prophet and an outstanding medicine woman. She was the sister to Chief Victorio. She was also known as a “shield to her people.” History has it that Lozen was able to use her powers in battle to learn the movements of the enemy and that she helped each band of Apaches to successfully avoid capture. After Victorio’s death, Lozen continued to ride with Chief Nana and eventually joined forces with Geronimo’s band until she finally surrendered with the last band of Apaches in 1886. She died of an illness in Mount Vernon Barracks in Mobile, Alabama. Today, Lozen’s descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Cochise (?-1874) was born in present-day Arizona. Cochise led the Chiricahua band of the Apache during a period of violent social upheaval. In 1850, the United States took control over the territory that today comprises Arizona and New Mexico. Not hostile to the white settlers at first, he kept the peace. Cochise is reputed to have been the strategist and leader who was never conquered in a battle. For 10 years Cochise and his warriors fought the white settlers. Cochise surrendered to U.S. troops in 1871. Upon his death, he was secretly buried somewhere in or near his impregnable fortress in the Dragoon Mountains. His descendants reside on the Mescalero Apache Reservation.

Within our homeland lie the four sacred mountains:

Sierra Blanca, Guadalupe Mountains, Three Sisters Mountain and Oscura Mountain Peak.

These four mountains represent the direction of everyday life for our Apache people. Our grandparents would often speak of the place called White Mountain. It was there that the creator gave us life and it is a special place. It was on White Mountain, according to legend, that White Painted Woman gave birth to two sons, Child of Water and Killer of Enemies. They were born during a turbulent rainstorm when thunder and lightning came from the sky.

Giant Monsters who wanted to kill them feared White Painted Woman and her sons, whom she raised to be brave and skilled. When they grew up to be men, they rose up and killed the monsters of the earth. There was peace and all human beings were saved.

Apache warriors hunted buffalo on the grassy plains. They hunted antelope on the prairies and deer in the mountains. They killed only what they needed for their immediate use. Their weapons were simple, but the men were swift and cunning hunters.

The Apache women were skillful providers. They could find water where others would die of thirst. They prepared meat and skins brought home by the men. While the men hunted, the women gathered wild plants, foods, nuts, and seeds. They picked fruit and berries, dug roots and harvested the plants.

The Apache women were skillful providers. They could find water where others would die of thirst. They prepared meat and skins brought home by the men. While the men hunted, the women gathered wild plants, foods, nuts, and seeds. They picked fruit and berries, dug roots and harvested the plants.

Apache people gathered the sweet fruit of the broad-leafed Yucca and pounded its roots in water to make suds for shampoo. The Apache women prepared a staple food from the heart of the Mescal plant. That is why the Spanish called the people “Mescalero,” the people who eat Mescal.

Apache people were kind to their children. They taught them good manners, kindness, fortitude and obedience. The children would play games that improved their dexterity.

Traditional Apache religion was based on the belief in the supernatural and the power of nature. Nature explained everything in life for the Apache people.

White Painted Woman gave our people their virtues of pleasant life and longevity. Apache religion, expressed in poetic terms, has passed from generation to generation. This is the background and the heritage of our people, the Mescalero Apaches.

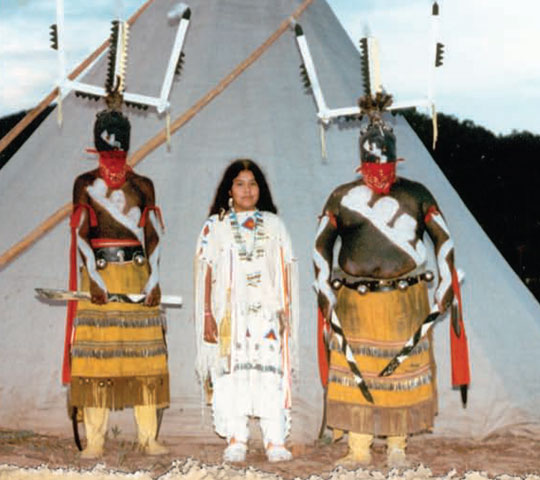

Mescalero Apache Puberty Rite Ceremony

One of the most traditional and sacred ceremonies practiced by the Mescalero Apache is the puberty rite ceremony. It is a four-day “Rite of Passage,” a ceremony that marks the transition of an individual from one stage of life to another, from girlhood to womanhood. A young girl celebrates her rite of passage with family-prepared feasts, dancing, blessings and rituals established hundreds of years ago. It emphasizes her upbringing which includes learning her tribal language and instilling, from infancy, a sense of discipline and good manners.

The ceremony binds the Mescalero Apache as people functioning as a cohesive unit. In the evenings, visitors can catch a glimpse of these important events, observing the masked dancers as they perform through singing and drumming.

The ceremony binds the Mescalero Apache as people functioning as a cohesive unit. In the evenings, visitors can catch a glimpse of these important events, observing the masked dancers as they perform through singing and drumming.

The ceremony is a major commitment for the family of the girl. Preparation often begins as much as a year in advance with the gathering of sacred items such as roasted mescal heart and pollen from water plants. A medicine man and medicine woman must participate. Dancers and singers must be arranged. Finding a ceremonial dress, either from a relative who previously went through the ceremony, or one that has been made for the occasion, is important, as it is a symbolic part of the rite. A significant part of the family’s obligation is to prepare a feast for each day of the ceremony and to share the bounty with all who attend. Gifts are also given.

It is said that this ceremony was given to the Apache people by White Painted Woman. When her people, the Apache, were hard pressed by evil monsters, White Painted Woman reared a son to destroy those creatures and to make the earth inhabitable for mankind. She is the model of heroic and virtuous womanhood. For the duration of the rite, the young girl dresses and acts like White Painted Woman. The girl is never referred to by her name, but is known as White Painted Woman.

Beginning at dawn on the first day, the young girl is guided and advised by a medicine woman through four days of formal observances and events. A teepee-shaped ceremonial structure is created by a medicine man and his male helpers. The structure is symbolically disassembled on the last day of the ceremony.

Beginning at dawn on the first day, the young girl is guided and advised by a medicine woman through four days of formal observances and events. A teepee-shaped ceremonial structure is created by a medicine man and his male helpers. The structure is symbolically disassembled on the last day of the ceremony.

The girl is dressed in the buckskin costume that she will wear for the following eight days. Her attendant supplies her with a length of reed that she must drink from for eight days, not allowing water to touch her lips. It is also forbidden for her to scratch herself with her fingernails. A wooden scratcher is provided that must be used for the same length of time. The girl is urged to talk little, to heed what is said to her, and to maintain a dignified manner. By the end of the fourth day, every possible experience, even sleep and the old age stick, has been mentioned in songs and prayers for the long life and good fortune for the young maiden and for the Apache people.

For four more days after the completion of the ceremony, the young maiden must continue to wear her ceremonial buckskins and must not wash or come in contact with water. The young maiden must continue to use her drinking tube and scratcher. At the end of this period the medicine woman washes her hair and body with suds of the yucca root. Then she changes into her ordinary clothing, equipped for her new stage in life and her role in the community.

Understanding Our Culture

In the Apache way of life, there is a belief that a dark side of life is present, as well as a light side. In the dark side of life there is misery, and nothing progresses for the Apache. Here in the light of life there is happiness; a world God created of peace and harmony. In this world of peace and harmony, everything progresses for our people. Our tribal enterprises, including Inn of the Mountain Gods Resort and Casino and Ski Apache are the an industries that provides for our people. These enterprises also contribute to the economy of the surrounding areas of the Southwest. Therefore, we ask our friends and visitors to respect our Apache way of life.

Snakes

Do not enter the reservation with snakes or any product made of snake skin or any part of the animal. The Apache do not communicate with this animal; it is considered a bad omen to have contact with a snake.

Bears

The bear is an animal the Apache do not have contact with because bears are highly respected. Never touch a bear, its waste materials, footprints, bedding area or anything the bear has touched. Do not call him by his name. The Apache people refer to him as “my grandfather” or “my uncle.” If you cross paths with the bear, tell him to go into the dense forest and live where no other entities set foot. Do not enter the reservation with the following: bearskin hides, claws or teeth.

Owls

The owl is a night creature and the Apache people do not have contact with this animal. Avoid having a night owl near you. It is considered a bad omen if an owl hoots near you day or night.

Respect for the Apache Elders

Our Apache elderly people are highly respected. They have earned the right to be known as elderly. The elderly preserve the traditions, culture, values and morals of the Mescalero Apache Tribe. Here are some examples of how an individual should approach the Apache elderly in everyday life. These examples are practiced by the younger generation and the middle-aged today on the reservation.

Staring

Do not stare or look at people with direct eye contact. This is perceived as being impolite. It is disrespectful to stare at all generations of our Mescalero Apache people. Pointing is also considered as impolite.

Affection

The Mescalero Apache people show respect for one another in the sense that little affection is expressed. Some Apaches do not mind being hugged and respond positively to appropriate gestures of affection; others might feel uncomfortable. Use good judgment and be sensitive to the signals they give you. Understand that some of our people may not want to be touched. This is not intended as disrespect or prejudice toward you.